Local Government

Town Council and Civic Matters

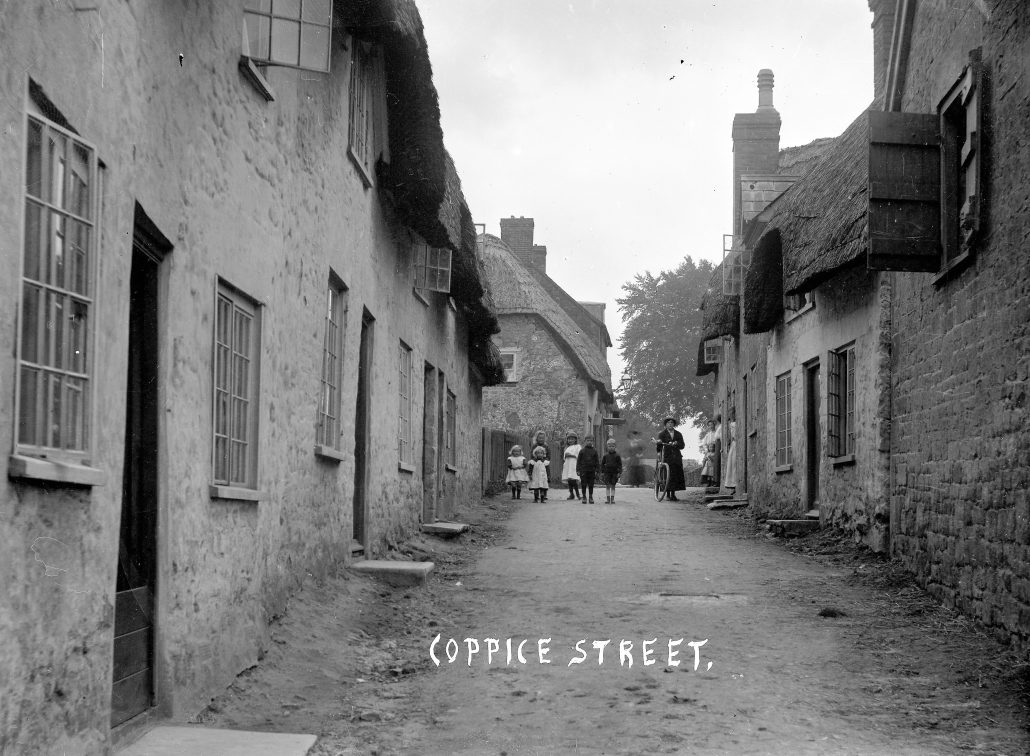

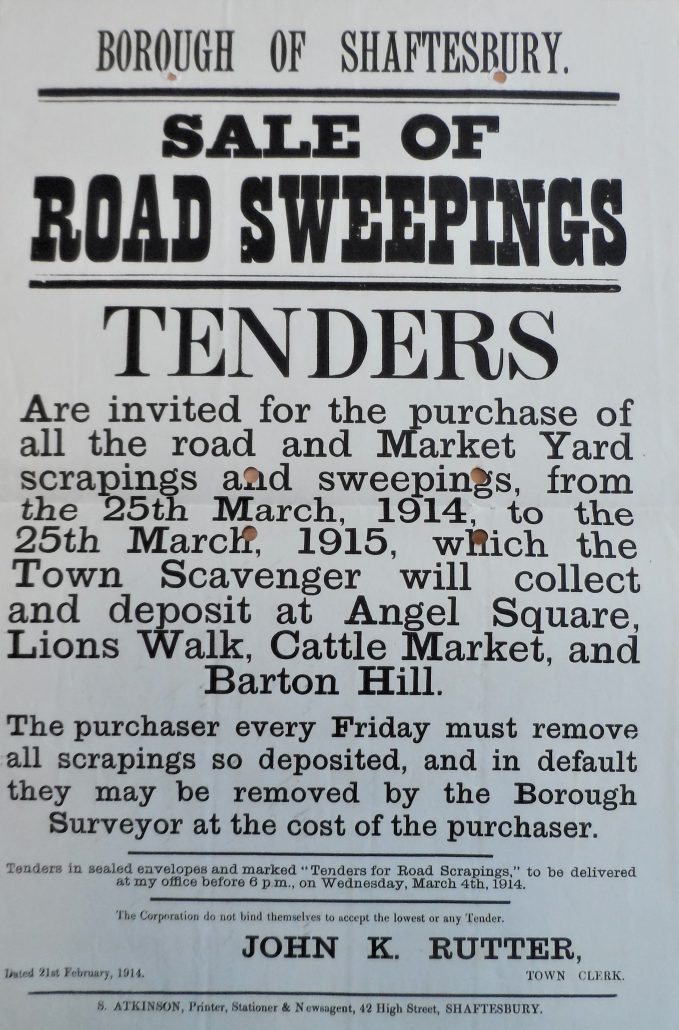

From 1914 to 1919 the Town Council voted upon issues concerning roads, housing, health, public services and the workhouse, and their meetings were reported every week in the Western Gazette. In addition it had to deal with the particular circumstances arising from the war. In early 1914 one of the main concerns of the town council was re-surfacing roads, as the increased amount of motor traffic, especially steam driven engines, was causing serious damage to traditional crushed stone road surfaces.

The council was advised to lay down tarmacadam, but it was expensive. However, borrowing money to pay for the cost was out of the question during the war.

1914

Local government boards and other boards were calling on all public bodies to reduce their expenditure wherever possible. Shaftesbury Town Council was already saving money by discontinuing street lighting, saving £250 (equivalent to £20,000 in 2017) per year.

The Lighting Committee lost a motion to provide public lamps at five dangerous sites in the town as it would cost money, and because lighting the town might increase the threat of Zeppelin raids. All vehicles were required to have lighting and many of the minor cases heard in the Shaftesbury Petty sessions related to lighting offences.

The council agreed in 1914 that the Town Hall could be used for recruiting soldiers, and the Market Hall for drill practice. By Christmas, pub opening hours were temporarily reduced, closing at 9 pm, due to the large number of recruits in the town. Drunkenness among recruits was common, as pubs and local people ‘treated’ the men who were billeted in the town, and the town’s numbers swelled at weekends as men from the nearby camps came for some entertainment.

1915

A letter was received by the Town Council, requesting that buckets should be placed around the town, to cater for the Nelson Battalion shortly to be billeted in the town.

February 11th 1915

From Lieutenant Commr Primrose

Nelson Battalion

1st Royal Naval Brigade Camp

Blandford

Dear Sir

With reference to my call upon you regarding the proposed one night’s billeting of the Nelson Battalion in Shaftesbury on Wednesday night, 17th inst.,I now write to ask you if you can possibly make arrangements through the Borough Sanitary Engineer, for latrine buckets to be placed in convenient positions to our billets, these buckets to be removed by the Borough Authorities on Thursday morning after we leave. If you could manage to arrange this, what would be the expense?

In the various billets, the lavatory accommodation is insufficient for the number of men, and we consider the provision of latrine buckets the most sanitary way out of the difficulty. The buckets would be required in the following places:

Market Hall 10 buckets …………………………….Town Hall 4 buckets

Hill and Boll’s Garage 2 buckets ……………… Cann Schools 4 buckets

If you can manage to arrange this, it will be a great help to me.

Thanking you for the trouble you have taken and hoping to get an answer by return

I am, Yours faithfully

R Clifford Primrose

Lt Commander

To

The Town Clerk Shaftesbury

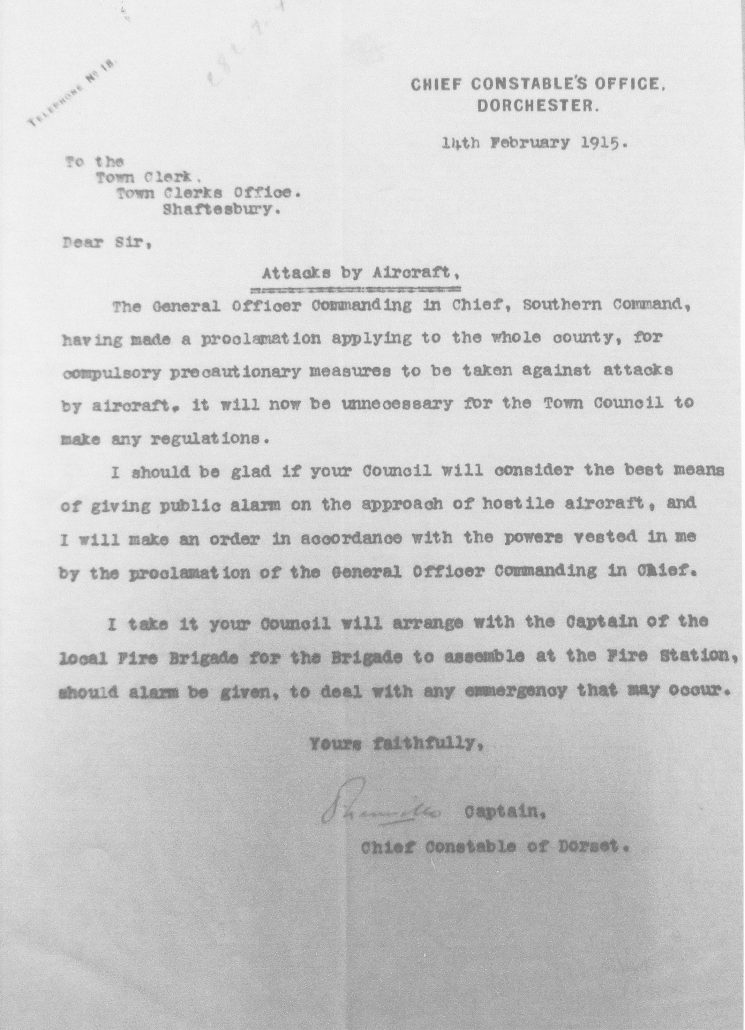

Shortly afterwards the Town Clerk received a letter from the Chief Constable’s Office in Dorchester, warning of the danger of attacks from aircraft, and the need to alert the public in the event of enemy action. The Fire Brigade was required to ready themselves as soon as the public alarm was given. The public were advised to shelter in cellars, and to cover all lights at night. Town lighting was to be extinguished as soon as the alarm went off. Drivers were asked to minimise using lights, and consequently there were several accidents at night. The police alone were to be responsible for sounding the alarm, to prevent scares or practical jokers.

1916

In 1916 the Town Hall clock was silenced at night at the request of the police, under the Defence of the Realm Act. The council gave £10 to the memorial fund for Lord Kitchener who drowned off the Orkney Islands in June when his ship hit a German mine.

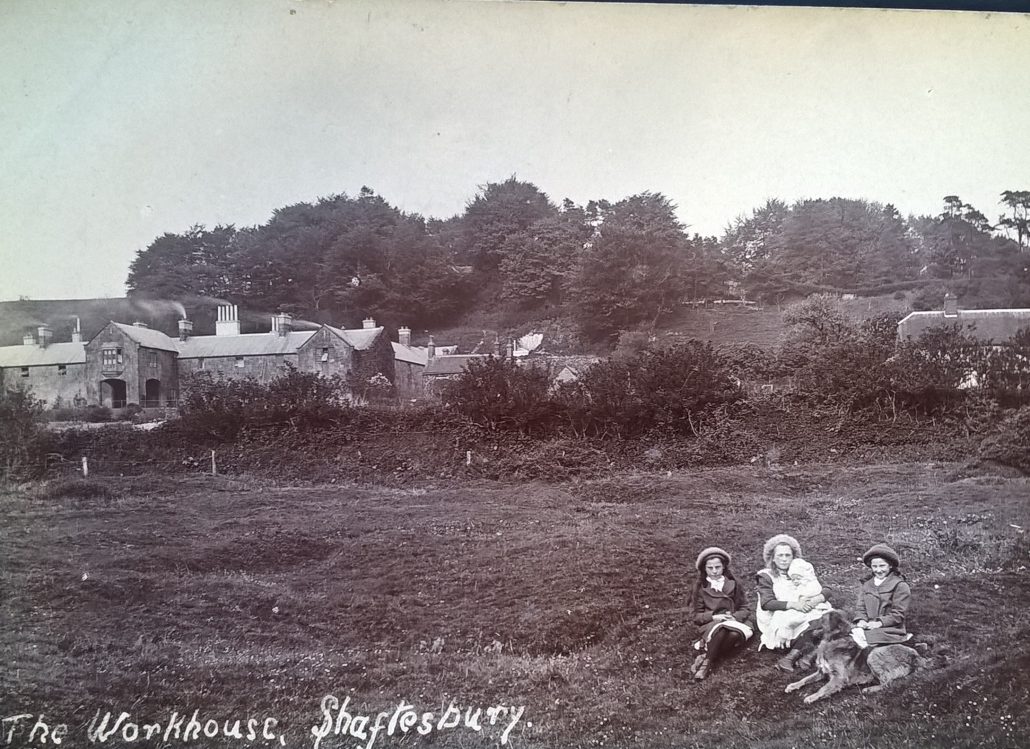

In August 1916 the Poor Yard in St James was ordered to be closed, and the houses there were subsequently knocked down and replaced.

1917

In 1917 the River Stour flooded in Gillingham, and roads in Cann, Margaret Marsh and Fontmell Magna were seriously damaged by traction engine traffic servicing the Salisbury, Semley and Gillingham Dairy Company. The local surveyor was asked to obtain German prisoners-of-war to work in the quarries, extracting stone for road surfacing and repairs. Messrs Marsh and Barter were paid £39 (worth £3200 in 2017) to spray the streets with water in dry weather, as the council was unable to afford the new asphalt surface which was their preferred option.